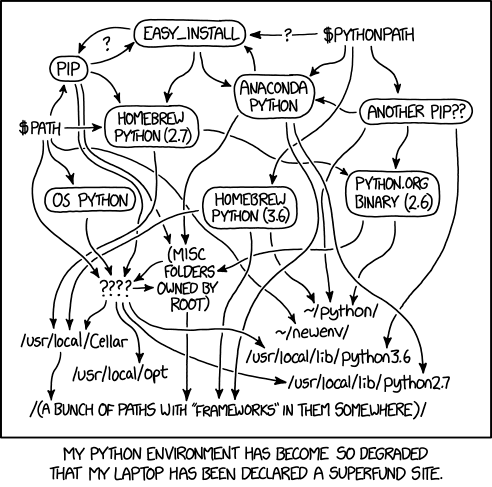

Anyone who works on Python projects and uses various packages will sooner or later have to deal with different versions of packages across different branches and projects. Because each project has its own set of dependencies, it’s a good practice to avoid mixing them. If all the dependencies are installed together in a single Python environment, then it will be difficult to discern where each one came from. In the worst cases, two different projects may depend on two different versions of a package, but with Python you can only have one version of a package installed at one time. What a mess! Virtual environments address this issue. A virtual environment, put simply, is an isolated working copy of Python which allows you to work on a specific project without worry of affecting other projects.

Overview

Python is considered a “batteries included” language. In other words, the Python standard library includes an extensive set of packages and modules to help developers with their scripts and applications. At the same time, Python has a very active community that contributes an even bigger set of packages that can help you with your development needs. These packages are published to the Python Package Index, also known as PyPI, which hosts an extensive collection of packages that include development frameworks, tools, and libraries.

At its core, the main purpose of Python virtual environments is to create an isolated environment for Python projects. This means that each project can have its own dependencies, regardless of what dependencies every other project has. You can think of a virtual environment as a carbon copy of a base version of Python. If you’ve installed Python 3.7.3, for example, then you can create many virtual environments based off of it. When you install a package in a virtual environment, you do it in isolation from other Python environments you may have. Each virtual environment has its own copy of the Python executable. Sanitary environment management practice reduces dependency version conflicts between your projects and keeps the base development environment from becoming bloated with packages:

The whole story of Python environments can be broken down into the following three levels:

- Package Management: Package management tools help you download and install third-party packages and their dependencies. They mostly work in tandem with virtual environments, isolating the packages you install in one Python environment from another. Examples are

pip,pipenv,poetry, andconda. - Virtual Environments: Tools that allow you to work on multiple projects in parallel, building on ‘carbon copies’ of the same Python version, but with different package dependencies. Examples are

venv,pyenv-virtualenv,pipenv, andconda. - Python Version Management: Tools that allow you to accomodate several different versions of Python in parallel, such as

pyenvandconda.

We will now tackle these levels and related tools in the following three sections before spending a final secion on conda, which lives more or less in a parallel universe to the other tools.

Package Management

For many Python projects one actually needs a number of third-party packages. Those packages may have their own dependencies in turn. In the early days of Python, using packages involved manually downloading files and pointing Python at them. Today, we’re fortunate to have a variety of package management tools available to us. Let’s start with a brief overview:

pip(“pip installs packages”) has been the de facto standard for package management in Python for several years. Python incorporatedpipinto the standard distribution starting in version 3.4.pipautomates the process of downloading packages and making Python aware of them.pipenvis a dependency manager for Python projects. Whilepipcan install Python packages,pipenvis recommended as it is a higher-level tool that simplifies dependency management for common use cases. It automatically creates and manages avirtualenvfor your projects, as well as adds/removes packages from yourpipfileas you install/uninstall packages. It also generates the importantpipfile.lock, which is used to produce deterministic builds.poetryis anotherpipalternative that is gaining a lot of traction. Likepipenv, it simplifies package version management and separates development vs production dependencies, and it works by isolating those dependencies into a virtual environment. It also goes beyond package management, helping you build distributions for your applications and libraries and deploying them to PyPI.

pip is the central tool for installing and uninstalling packages. The pip install command always installs the latest published version of a package, but sometimes, you may want to install a specific version that you know works with your code. You want to create a specification of the dependencies and versions you used to develop and test your application, so there are no surprises when you use the application in production. A common way to specify project dependencies for pip is with a requirements.txt file. Requirement files allow you to specify exactly which packages and versions should be installed.

The pip freeze command allows you to get exact versions for all 3rd party libraries currently installed, including the sub-dependencies pip installed automatically. So you can freeze everything in development to ensure that you have the same environment in production. We could run pip freeze > requirements.txt to output a list of installed packages to a text file, and use that same text file to install everything an app needed with pip install -r requirements.txt. But pip doesn’t include a way to isolate packages from each other.

Virtual Environments

Python, like most other modern programming languages, has its own unique way of downloading, storing, and resolving packages (or modules). There are a few different locations where these packages can be installed on your system. For example, most system packages are stored in a child directory of the path stored in sys.prefix. Third party packages installed using pip are typically placed in one of the directories pointed to by site.getsitepackages. By default, every project on your system will use these same directories to store and retrieve site packages (third party libraries), irrespective of the specific version needed. If two projects were developed with dependencies on different versions of the same package, we are (potentially) heading for a conflict.

Virtual environments are key to preventing such conflicts. The tool landscape here is a little confusing, so let’s also kick this section off with a list of tools:

pipenvis a rather new tool (born in 2017) that aims to bring the best of all packaging worlds to the Python world.pipenvis a dependency manager for Python projects. Whilepipcan install Python packages,pipenvis recommended as it is a higher-level tool that simplifies dependency management for common use cases. It automatically creates and manages avirtualenvfor your projects, as well as adds/removes packages from yourpipfileas you install/uninstall packages. It also generates the importantpipfile.lock, which is used to produce deterministic builds.pipenvis primarily meant to provide users and developers of applications with an easy method to setup a working environment. Windows is considered a first-class citizen.virtualenvis a tool to create isolated Python environments.virtualenvcreates a folder which contains all the necessary executables to use the packages that a Python project would need. It can be used standalone, in place ofpipenv. Since Python 3.3, a subset ofvirtualenvhas been integrated into the standard library under thevenvmodule. Note though, that thevenvmodule does not offer all features ofvirtualenv(e.g. cannot create bootstrap scripts, cannot create virtual environments for other Python versions than the host Python, not relocatable, etc.).pyenv-virtualenvenhancespyenvwith a subcommand for managing virtual environments. You can configurepyenv-virtualenvso that it auto-activates the right environments as you switch to different directories.virtualenvwrapperprovides a set of commands which makes working with virtual environments much more pleasant. It also places all your virtual environments in one place.

Let’s take a look at pipenv. First, let’s install it:

$ pip install pipenvOnce you’ve done that, you can effectively forget about pip since pipenv essentially acts as a replacement. It also introduces two new files, the pipfile (which is meant to replace requirements.txt) and the pipfile.lock (which enables deterministic builds acts as a snapshot of the precise set of packages installed, including direct dependencies as well as their sub-dependencies). pipenv uses pip and virtualenv under the hood but simplifies their usage with a single command line interface.

pipenv manages dependencies on a per-project basis. To install packages, change into your project’s directory and install the package like this:

$ cd myproject

$ pipenv install <package>This will create a pipfile if one doesn’t exist. If one does exist, it will automatically be edited with the new package you provided. Next, activate the project’s virtual environment by running pipenv shell:

$ pipenv shell

$ python --versionThis will spawn a new shell subprocess, which can be deactivated by using exit. It will also create a virtual environment if one doesn’t already exist. pipenv creates all your virtual environments in a default location. The following commands can sometimes be helpful:

$ pipenv --venv # Find out where your virtual environment is

$ pipenv --where # Find out where your project home is

$ pipenv graph # Print a tree-like structure showing your dependenciesPython Version Management

Something many Python developers will eventually run into is the need to run multiple versions of Python in parallel. As an example, macOS and most Unix operating systems come with a version of Python installed by default. This is often called the system Python. The system Python works just fine, but it’s usually out of date. Still it is important that you leave the system Python as the default, because many parts of the system rely on the default Python being a specific version.

pyenv is a mature tool for installing and managing multiple Python versions. The installation process is described here and here. pyenv did not originally support Windows, but by now you can use pyenv-win. After you’ve got pyenv installed, you can take a look at Python versions installed so far:

$ pyenv versions

* systemOnly the system environment is found, with the default Python installed along with the operating system. Let’s check it’s version:

$ python --version # Or: python -V

Python 2.7.10Let’s install another Python version, using pyenv:

$ pyenv install 3.6.8 # This may take some time

$ pyenv install 3.7.3 # This may take some time

$ pyenv versions

* system

3.6.8

3.7.3The * indicates that the system Python version is active currently. Each version that you have installed using pyenv is located nicely in the pyenv root directory:

$ ls ~/.pyenv/versions/

3.6.8 3.7.3Removing a particular Python version can be simply done like this:

$ rm -rf ~/.pyenv/versions/3.6.8or by using a proper pyenv command:

$ pyenv uninstall 3.6.8Virtual environments and pyenv are a match made in heaven. pyenv has a plugin called pyenv-virtualenv that makes working with multiple Python version and multiple virtual environments a breeze. An opinionated workflow can look as follows.

Create a virtual environment:

$ pyenv virtualenv <python_version> <environment_name>Technically, the <python_version> is optional, but you should consider always specifying it so that you’re certain of what Python version you’re using. The <environment_name> is just a name for you to help keep your environments separate. A good practice is to name your environments the same name as your project. For example, if you were working on myproject and wanted to develop against Python 3.6.8, you would run this:

$ cd myproject

$ pyenv which python

/usr/bin/python

$ pyenv virtualenv 3.6.8 myprojectNow that you’ve created your virtual environment, using it is the next step. Normally, you should activate your environments by running the following:

$ pyenv local myproject

$ python -V

.../.pyenv/versions/project1/bin/pythonThis creates a .python-version file in your current working directory. If during installationof pyenv you have added the following lines to your ~/.bashrc (or ~/.zshrc or ~/.bash_profile)

eval "$(pyenv init -)"

eval "$(pyenv virtualenv-init -)"then pyenv will automatically activate and deactivate environments when changing directories. You can verify this by running the following:

$ pyenv which pythonIf you did not configure your shell accordingly, you can still manually activate/deactivate your Python versions with this:

$ pyenv activate <environment_name>

$ pyenv deactivateThis is what pyenv-virtualenv is actually doing when it enters or exits a directory with a .python-version file in it.

Conda

conda is the package and environment management tool for Anaconda Python installations that runs on Windows, Mac OS and Linux. conda is a completely separate tool to pip or virtualenv, but provides many of their combined features in terms of package management, virtual environment management and deployment of binary extensions. conda does not install packages from PyPI and can install only from the official Anaconda repositories, or anaconda.org (a place for user-contributed conda packages), or a local (e.g. intranet) package server. However, note that pip can be installed into, and work side-by-side with conda for managing distributions from PyPI. Here are some reasons why people recommend to use conda:

condaprovides prebuilt packages, avoiding the need to deal with compilers, or trying to work out how exactly to set up a specific tool. Fields such as Astronomy usecondato distribute some of their most difficult-to-install tools such as IRAF. However, TensorFlow 2.0 can currently only be installed throughpip, there are nocondapackagescondais cross platform, with support for Windows, MacOS, GNU/Linux, and support for multiple hardware platformscondaallows for using other package management tools (such as pip) insidecondaenvironments, where a library or tools is not already packaged forconda- Anaconda provides commonly used data science libraries and tools, such as R, NumPy, SciPy and TensorFlow built using optimised, hardware specific libraries (such as Intel’s MKL or NVIDIA’s CUDA), which provides a speedup without having to change any of your code.

To create an environment with conda for Python development, run:

$ conda create --name conda-env pythonThe command above will create a new conda environment called “conda-env” and install the most recent version of Python. If you wish, you may specify a particular version of Python for conda to install as follows

$ conda create -n conda-env python=3.7You can also specify which versions of packages you’d like to install:

$ conda create -n conda-env python=3.7 numpy=1.16.1 requests=2.19.1It’s recommended to install all the packages you want to include in an environment at the same time to help avoid dependency conflicts. However, you can also add additional packages later on like this:

(conda-env) % conda install pandas=0.24.1 # From inside an active environment

conda install -n conda-env pandas=0.24.1 # From your default shellLikewise, you can update the packages in an environment in two ways:

(conda-env) % conda update pandas # From inside an active environment

conda update -n conda-env pandas # From your default shellIt is strongly recommend to install packages from inside and active environment, as it removes the danger of unintentionally installing packages system-wide. When conda installs a package into an environment it also installs any required dependencies. Last, you can activate and deactivate your environment like this:

$ conda activate conda-env

(conda-env) $ # Fancy new command prompt

(conda-env) $ conda deactivate

$Environments created with conda live by default in the envs/ folder of your conda directory, whose path will look something like:

.../Users/$USERNAME/anaconda3/envsHowever, you may also choose another approach, as described here. You can control where a Conda environment lives by providing a path to a target directory when creating the environment. For example to following command will create a new environment in a sub-directory of the current working directory called env.

$ conda create --prefix ./env ipython=7.13 matplotlib=3.1 pandas=1.0 python=3.6You activate an environment created with a prefix using the same command used to activate environments created by name.

$ conda activate ./envYou activate an environment created with a prefix using the same command used to activate environments created by name.

$ conda activate ./envAdvantages that may be seen in this approach are the following:

- Presence of sub-directory makes it easy to tell if your project utilizes an isolated environment

- Makes your project more self-contained as everything including the required software is contained in a single project directory

- You can use the same name for all your environments

- If you use

envas the name of the sub-directory that contains yourcondaenvironment it will be automatically ignored by the default Python.gitignorefile used on GitHub

The overall process in this approach would look like this:

$ mkdir project-dir

$ cd project-dir

project-dir $ conda create --prefix ./env python=3.6 matplotlib=3.1 ....

project-dir $ conda activate ./envIf you go for this approach you should also update your .condarc file as described here. If you created your conda environment using the --prefix option to install packages into a particular directory, then you will need to use that prefix in order to list the contents of that environment:

$ conda list --prefix /path/to/conda-envIn the more general case you would list the contents of an environment like this:

$ conda list --name basic-conda-envIn order to list all of your existing environments you would use the following command:

$ conda env listRemoving an environment is done like this, depending on how it was set up:

$ conda remove --name my-first-conda-env --all

$ conda remove --prefix /path/to/conada-env/ --allLinks to documentation and further reading

Documentation

- PyPA guides: here, here, and here

pipenv: https://pipenv.readthedocs.io/en/latest/virtualenv: https://virtualenv.pypa.io/en/stable/venv: https://docs.python.org/3/library/venv.htmlconda: https://docs.conda.io/…/manage-environments.html

Overview articles

- Python Virtual Environments: A Primer

- An Effective Python Environment: Making Yourself at Home

- Python Environment 101: How are pyenv and pipenv different and when you should be using them

- What Is Pip? A Guide for New Pythonistas

- Using Python environments in VS Code

- Using Virtual Environments in Jupyter Notebook and Python

Articles on pyenv

Articles on pipenv

- Pipenv: A Guide to the New Python Packaging Tool

- Why Python devs should use Pipenv

- Pipenv & Virtual Environments

- Virtual Environments for Data Science: Running Python and Jupyter with Pipenv

Articles on conda

- Introduction to Conda for (Data) Scientists

- Setting Up Python for Machine Learning on Windows

- The Definitive Guide to Conda Environments

- Why you need Python environments and how to manage them with Conda

- Setting Up Python for Machine Learning on Windows | Understanding Conda Environments