This is the first post in short series that I write on the basics of differential or Riemannian geometry. Differential geometry is a key mathematical foundation of general relativity, and the terminology presented here is a prerequisite for reading some of the more advanced textbooks, such as the ones by Carroll, MTW, Wald, Straumann or Hawking/Ellis. Here I start with differentiable manifolds. The following posts will cover tangent spaces, tensors, covariant derivatives and parallel transport. The presentation will be informal, focusing mostly on motivation, definitions and key facts, not on mathematical proofs.

Differentiable Manifolds

In non-relativistic physics as well as in special relativity, space and time can be considered as vector spaces per se, i.e., the points of spacetime are in one-to-one correspondence with certain position vectors. However, in the theory of general relativity, in which the spacetime becomes a curved dynamic object, this concept fails. In general relativity the spacetime is represented by a so-called manifold \(\mathcal{M}\)—a set of points which locally still looks like a Minkowski vector space but which may possess nontrivial curvature over extended regions and does not have a vector space structure globally, meaning that the points on the manifold can no longer be described by vectors. However, on short distances the spacetime still looks like a planar vector space, and vectors can therefore be used to specify directions in space-time.

Manifolds (or differentiable manifolds) are one of the most fundamental concepts in mathematics and physics. In many situations such a manifold is embedded in a higher-dimensional flat vector space such as e.g. the two-dimensional spherical surface is embedded in \(\mathbb{R}^3\). A space is called flat if it does not have any curvature. Vector spaces are by definition flat. It turns out that there are abstract manifolds that cannot be embedded into a higher dimensional vector space. The 4-dimensional curved spacetime of general relativity is such an abstract manifold that can not be embedded in a superordinate 5-dimensional (flat) vector space.

Modern differential geometry thus searches for an intrinsic description of the curved space, without resorting to a surrounding embedding space. A very important idea is to imagine that there are “flat” observers living entirely within the surface \(\mathcal{M}\). These observers cannot see the larger space and describe the surface \(\mathcal{M}\) exclusively through the relationships between the points of \(\mathcal{M}\), without referring to any embedding into a larger space. Another argument in favor of the intrinsic description is that according to General Relativity, we are observers living in a four-dimensional curved manifold (the spacetime), and we do not directly see any higher-dimensional space in which our spacetime is embedded as a “hypersurface.” Therefore, we need a way to describe the properties of our spacetime in terms of intrinsic measurements, i.e. measurements performed entirely within the spacetime.

The informal idea of a manifold \(\mathcal{M}\) with dimension \(n\) is that of a space consisting of patches that look locally like the Euclidean space \(\mathbb{R}^n\), and are smoothly sewn together.

In other words, somewhat terse and technical:

The manifold \(\mathcal{M}\) can be covered by a countable set of open subsets \(U_1, U_2 \ldots\subset \mathcal{M}\) such that every point \(x \in \mathcal{M}\) is contained in at least one \(U_\alpha\).

For every subset \(U_\alpha\) there is a homeomorphism \(\phi_\alpha\) (i.e. a mapping which is invertible and continuous in either direction) which maps \(U_\alpha\) into an open neighborhood of the image \(x = \phi_\alpha(p)\) in a copy of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) , viz. \(\phi_\alpha: U_\alpha \to \phi(U_\alpha)\), \(U_\alpha \subset \mathcal{M}\) and \(\phi_\alpha(U_\alpha) \subset \mathbb{R}^n\).

The original point on \(\mathcal{M}\) is denoted by \(p\). Its image in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) is denoted by \(x\).

This construction yields an atlas of charts, or local coordinate systems.

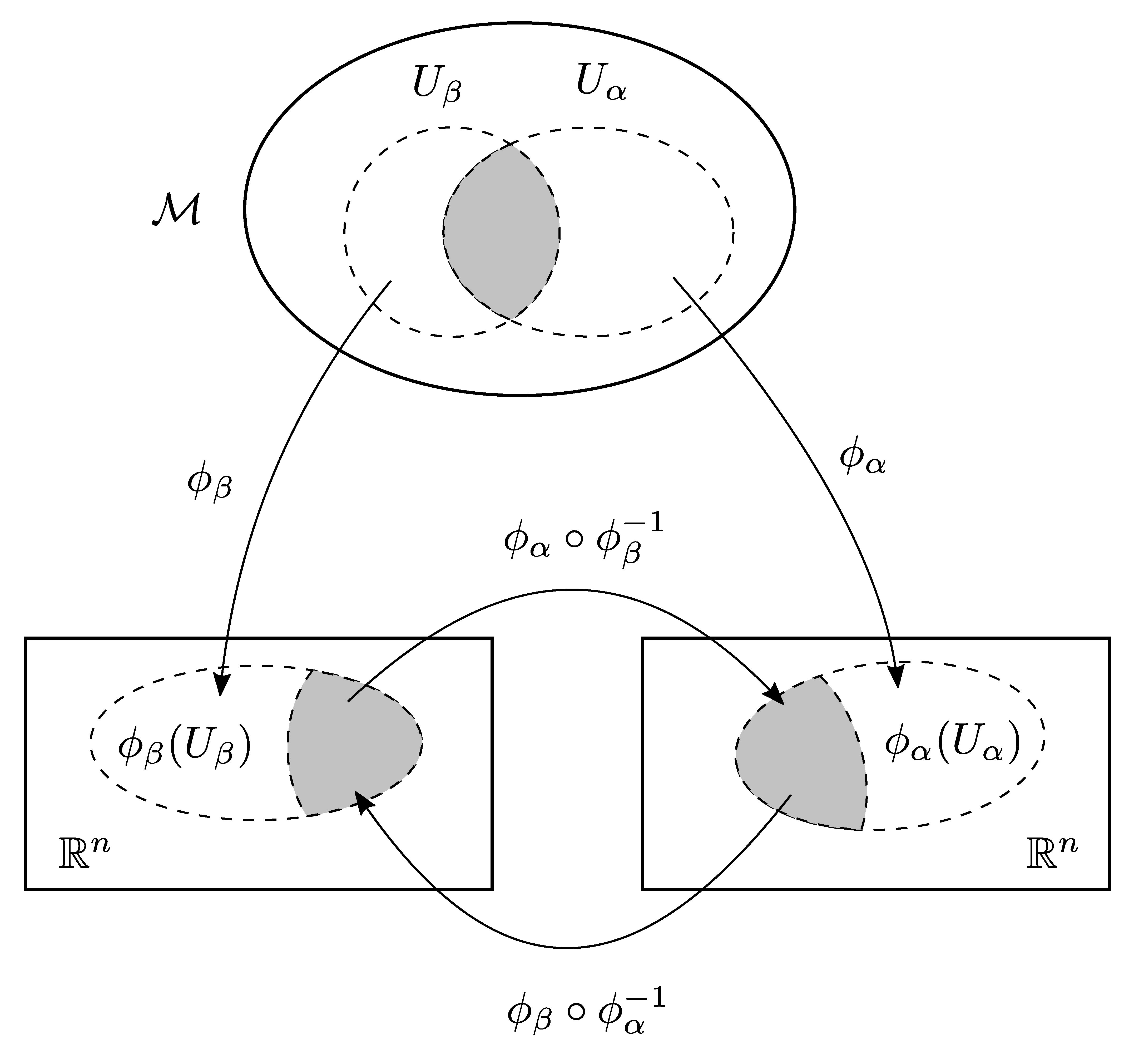

Any two charts overlap smoothly, that is to say, every transition mapping \((\phi_\beta \circ \phi_\alpha^{-1})\) is a diffeomorphism, which, by definition, links the image \(\phi_\alpha(U_\alpha)\) in the \(\alpha\)-th copy of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) with the image \(\phi_\beta(U_\beta)\) in the \(\beta\)-th copy of \(\mathbb{R}^n\). Recall that a diffeomorphism is an invertible mapping which is smooth (\(C^\infty\)) and whose inverse is also smooth.

As a further assumption, let every chart that has smooth overlap with all other charts be contained in the atlas.

This defines a differentiable structure \((\mathcal{M}, \mathcal{A})\) consisting of a manifold and a maximal atlas.

This was quite dense. Let's walk through these points again, in more detail, and add remarks and pictures.

As we set out to define differentiable manifolds and remove any reference to an ambient Euclidean space, we would still like close points on the manifolds to have close coordinates. But that requires some notion of nearness in \(\mathcal{M}\), which can be given by the definition of a distance between points of \(\mathcal{M}\) or, more generally, by assigning a topology to \(\mathcal{M}\). Not every topological space can fit the bill of usefulness for differential geometry, so we require some additional properties of what types of topological spaces we will consider. We first impose the requirement of having a cover of open sets, each of which is homeomorphic to an open set in a Euclidean space.

An \(n\)-dimensional topological manifold \(\mathcal{M}\) is a Hausdorff topological space with a countable base that is locally homeomorphic to \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

This means that for all \(p \in \mathcal{M}\), there exists an open neighborhood \(U\) of \(p\) that is homeomorphic to an open set of \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

In other words, for every point \(p \in \mathcal{M}\) there is an open neighborhood \(U\) of \(p\) and a homeomorphism \(\phi: U \to V\) wich maps \(U\) onto an open set \(V \in \mathbb{R}^n\).

The condition that \(\mathcal{M}\) be Hausdorff is there basically to express our intuition of space as “infinitely divisible”, so that we can separate points with disjoint open sets. Hausdorff topologies coincide with our intuition that points are isolated objects; other sorts of topologies are generally considered to be pathological (at least by non-topologists). The condition that the cover be countable is there for a technical reason having to do with extending locally defined quantities to globally defined ones.

In the definition of a topological manifold, a given homeomorphism \(\phi\) of a neighborhood \(U\) of \(\mathcal{M}\) with a subset \(V\) of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) provides a local coordinate system or coordinate patch. As one moves around on the manifold, one passes from one coordinate patch to another. This is summarized in the following definition:

If \(\mathcal{M}\) is a topological manifold and \(\phi : U \to V\) is a homeomorphism which maps an open subset \(U \subset \mathcal{M}\) onto an open subset \(V \subset \mathbb{R}^n\), then \(\phi\) is a chart or coordinate system or \(\mathcal{M}\).

\(U\) is called the domain or coordinate neighborhood of the chart. \(V=\phi(U)\) is the image of \(\phi\).

The inverse map \(\phi^{-1}\) is called parameterization.

The coordinates \((x^1, \dots , x^n)\) of the image \(\phi(p) \in \mathbb{R}^n\) of a point \(p \in U\) are called the coordinates of \(p\) in the chart (see remark below).

Let's pause and add a few remarks:

We have required \(\phi\) to be one-to-one. Since any map is onto its image, the map \(\phi : U \to \phi(U)\) is onto. Therefore, since \(\phi\) is both one-to-one and onto, it is also invertible.

Despite the fact that technically a chart is a function \(\phi : U \to \mathbb{R}^n\), where \(U\) is an open subset of the manifold \(\mathcal{M}\), one sometimes refers to the chart \((U, \phi)\) to emphasize the letter to be used for the domain of \(\phi\).

Let \((U, \phi)\) be a coordinate chart with \(p \in U\) and suppose that \(\phi(p) = q\). If \(x^1, \dots , x^n\) are the standard coordinate functions on \(\mathbb{R}^n\) then \(q\) has coordinates \((x^1(q), \dots , x^n(q))\) on \(V=\phi(U)\). It is convenient and common to view the \(x^{i}\) as coordinate functions on \(U\) instead of \(V\) and to write \(\phi(p) = (x^1(p), \dots , x^n(p))\). However, as \(U\) generally does not live in Euclidean space, this is an abuse of notation and makes only sense if it is interpreted to mean \(\phi(p) = (x^1(q), \dots , x^n(q))\).

The charts must be sewn together smoothly. More precisely, if \(\phi_\alpha\) and \(\phi_\beta\) are two charts, then both define homeomorphisms on the intersection of their domains \(U_{\alpha\beta} := U_\alpha \cap U_\beta\). One thus obtains a homeomorphisms between two open sets in \(\mathbb{R}^n\), as shown in Figure~\ref{change-of-coordinates}. The homeomorphism \(\phi_{\alpha\beta} := \phi_\alpha \circ \phi_\beta^{-1}\) takes points in \(\phi_\beta(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta) \subset \mathbb{R}^n\) onto an open set \(\phi_\alpha(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta) \subset \mathbb{R}^n\).

Any pair of charts \(\phi_\alpha\) and \(\phi_\beta\) is compatible of class \(C^k\) or \(C^k\)-related if either \(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta = \emptyset\), or \(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta =\not\, \emptyset\) and the transition functions \(\phi_{\alpha\beta}\) and \(\phi_{\beta\alpha}\), with \(\phi_{\alpha\beta} := \phi_\alpha \circ \phi_\beta^{-1} : \phi_\beta(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta) \to \phi_\alpha(U_\alpha \cap U_\beta) \; ,\) are functions of class \(C^k\) between open subsets of \(\mathbb{R}^n\). They are also called change of coordinate or coordinate transformation.

For simplicity, we shall from now on always assume smooth mappings, i.e. differentiable mappings of class \(C^\infty\) on \(\mathbb{R}^n\) (the derivatives of all orders exist and are continuous).

A set of charts \(\left\lbrace \phi_\alpha | \alpha \in I \right\rbrace\), with some indexing set \(I\) and domains \(U_\alpha\), is called an atlas of \(\mathcal{M}\), if the \(U_\alpha\) constitute an open covering of \(\mathcal{M}\), i.e. \(\bigcup_{\alpha \in I} U_\alpha = \mathcal{M}\).

A chart is admissible to an atlas if it is \(C^\infty\)-related to every chart in the atlas.

An atlas is called maximal if it contains every chart that is admissible to it.

Again, some remarks:

An atlas is, in other words, a collection \(\mathcal{A} = \left\lbrace (U_\alpha, \phi_\alpha) \right\rbrace\) of pairwise compatible charts whose domains \(U_\alpha\) cover the manifold \(\mathcal{M}\).

Atlases give us the possibility to map an \(n\)-dimensional manifold onto subsets of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) and then to represent objects such as points in the usual way.

Atlases are not unique because there are infinitely many possible projections and partitions. So, if we want to compute an abstract property of a manifold with the help of maps, the result must be independent of the chosen representation, that is, it has to coincide for all possible atlases.

A chart is compatible with an atlas if adding the chart to the atlas yields again an atlas.

Two atlases are compatible if their union is again an atlas.

We are now able to complete our definitions:

An atlas \(\left\lbrace (U_\alpha, \phi_\alpha) \right\rbrace\) is called differentiable atlas if all chart transitions \(\phi_{\alpha\beta}\) are differentiable of class \(C^\infty\).

A maximal differentiable atlas is called a differentiable structure.

A differentiable (or smooth) manifold is a topological manifold with a differentiable structure.

Functions and Curves on Manifolds

Next, let us introduce various geometrical objects that are defined on smooth manifolds. There are many examples: functions such as the Lagrangian and Hamiltonian functions, curves on manifolds such as solution curves of equations of motion, vector fields such as the velocity field of a given dynamical system, forms such as the volume form that appears in Liouville’s theorem, and many more.

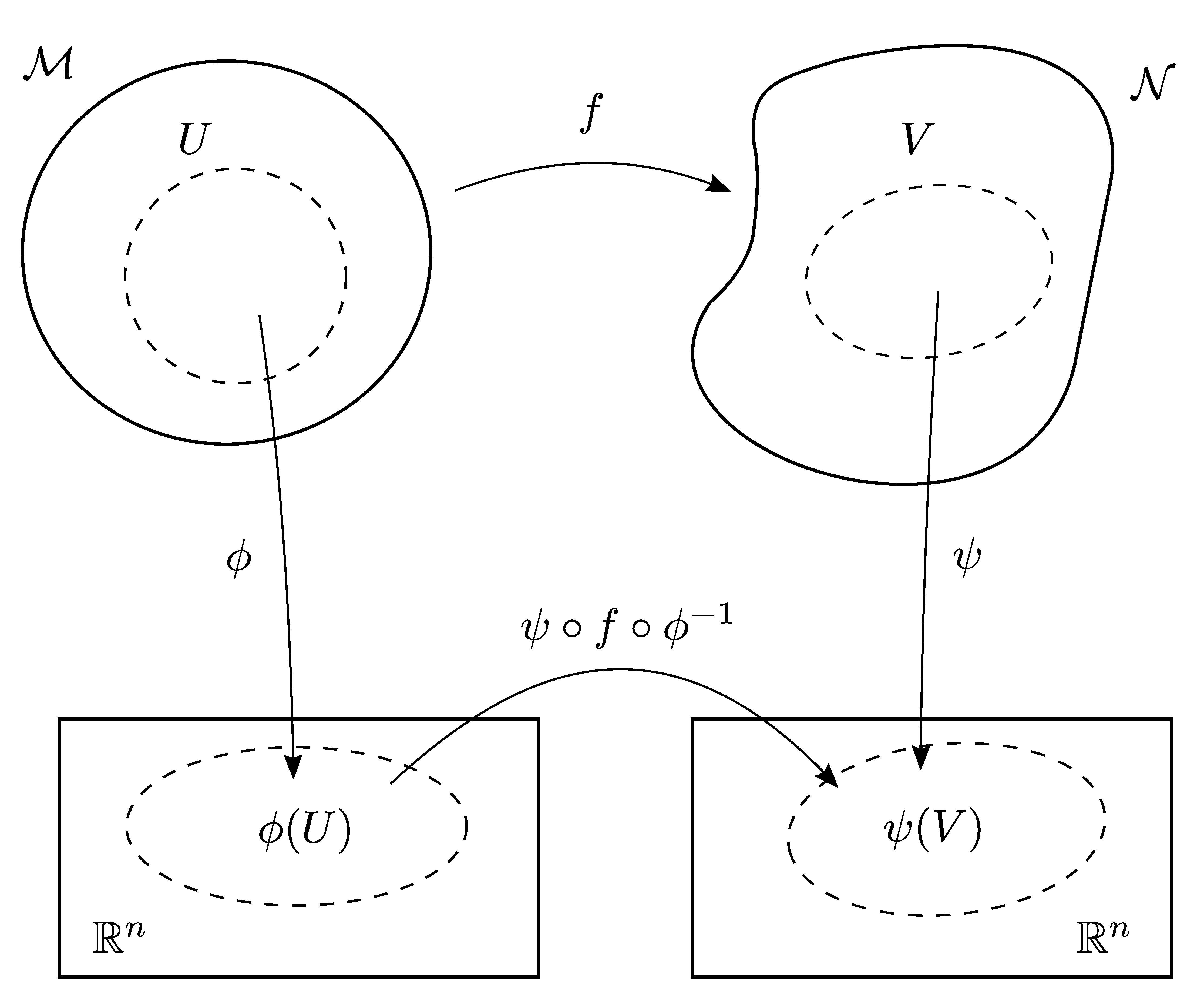

We start with a rather general notion: mappings \(f: (\mathcal{M},\mathcal{A}) \to (\mathcal{N},\mathcal{B})\) from a smooth manifold \(\mathcal{M}\) with atlas \(\mathcal{A}\) onto another manifold \(\mathcal{N}\) with atlas \(\mathcal{B}\) (where \(\mathcal{N}\) may be identical with \(\mathcal{M}\)). The point \(p\), which is contained in an open subset \(U\) of \(\mathcal{M}\), is mapped onto the point \(f(p)\) in \(N\), which, of course, is contained in the image \(f(U)\) of \(U\). Let's investigate what it means for such a function \(f\) to be differentiable (see Figure 2):

Let \(\mathcal{M}\) and \(\mathcal{N}\) be smooth manifolds of dimensions \(m\) and \(n\), respectively.

Let \(f: (\mathcal{M},\mathcal{A}) \to (\mathcal{N},\mathcal{B})\) be a map. Assume that \((\phi, U)\) is a chart from the atlas \(\mathcal{A}\), and \((\psi, V)\) a chart from \(\mathcal{B}\) such that \(f(U)\) is contained in \(V\).

The following composition is then a mapping between the Euclidean spaces \(\mathbb{R}^m\) and \(\mathbb{R}^n\), called the coordinate expression for \(f\):

\[\psi \circ f \circ \phi^{-1}: \phi(U) \subset \mathbb{R}^m \to \psi(V) \subset \mathbb{R}^n \, .\]

The mapping \(f\) is said to be smooth or differentiable if the coordinate expression has this property for every point \(p \in U\), every chart \((\phi, U) \in \mathcal{A}\), and every chart \((\psi, V) \in \mathcal{B}\), the image \(f(U)\) being contained in \(V\).

Note that from the definition it follows that a function between two manifolds cannot have a stronger differentiability property than do the manifolds themselves.

In linear algebra, where one studies the category vector spaces, one does not study properties of any kind of function between two vector spaces. Instead, we restrict the attention to linear transformations since they “preserve the structure” of vector spaces. Furthermore, from the perspective of linear algebra, two vector spaces \(V\) and \(W\) are considered the same (isomorphic) if there exists a bijective linear transformation between the two.

In the same way, in the category of differential manifolds, one is primarily interested in differentiable maps between these manifolds. The following definition is the equivalent notion of an isomorphism but for manifolds.

Let \(\mathcal{M}\) and \(\mathcal{N}\) be two differentiable manifolds. A diffeomorphism between \(\mathcal{M}\) and \(\mathcal{N}\) is a bijective function \(f : \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{N}\) such that \(f\) is differentiable and \(f^{-1}\) is differentiable. If a diffeomorphism exists between \(\mathcal{M}\) and \(\mathcal{N}\), we say that \(\mathcal{M}\) and \(\mathcal{N}\) are diffeomorphic.

In a sense, diffeomorphisms are to differentiable manifolds what homeomorphisms are to topological spaces, and what isomorphisms are to vector spaces. Let's now look at concrete examples which are relevant to the world of physics.

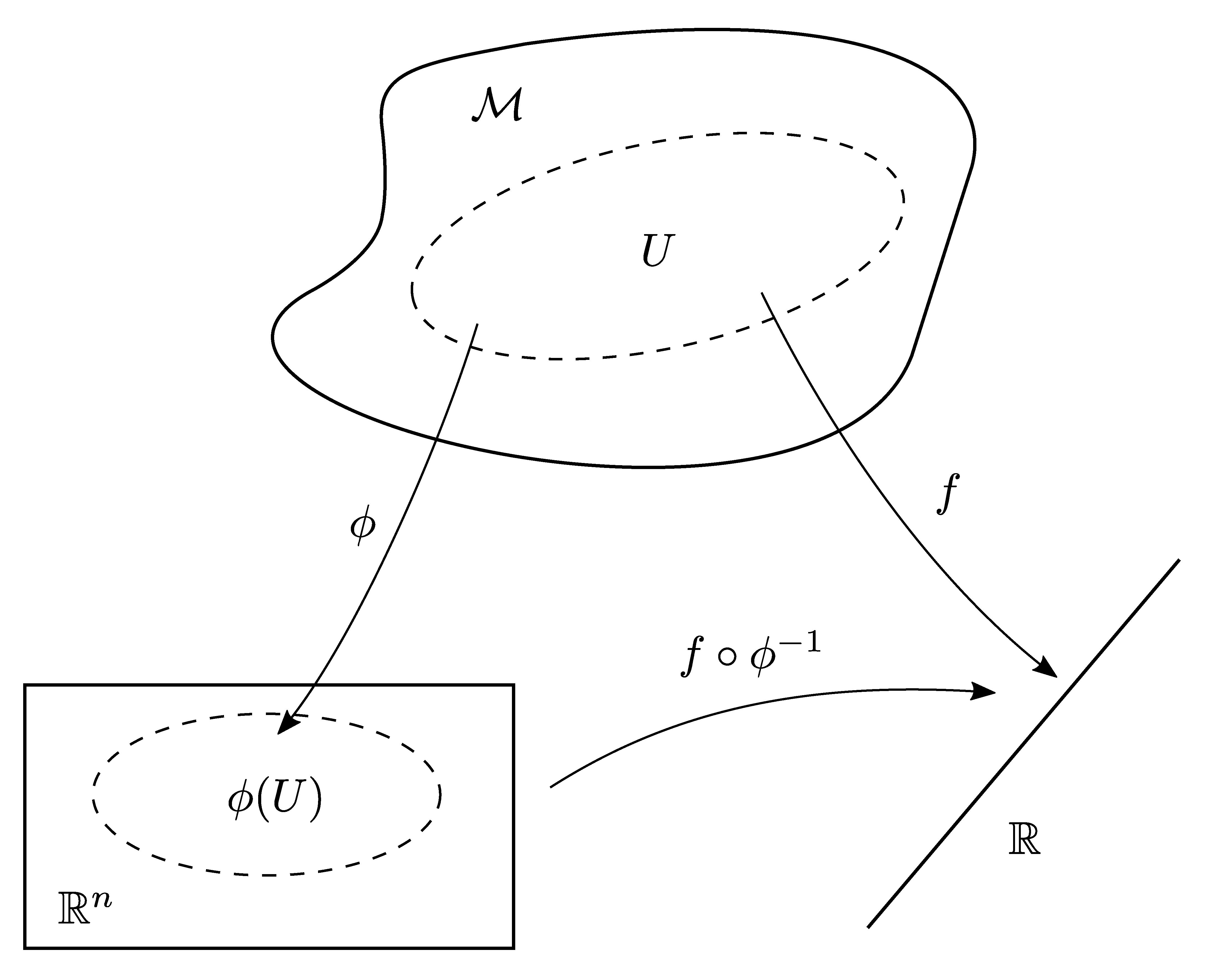

If the manifold \(\mathcal{N}\) to which \(f\) leads is \(\mathbb{R}\), then the chart mapping \(\psi\) is the identity. In this case \(f\) is a smooth function on \(\mathcal{M}\) (see Figure 3).

A smooth function on a manifold \(\mathcal{M}\) is a mapping from \(\mathcal{M}\) to the real numbers,

\[f : \mathcal{M} \to \mathbb{R} : p \in \mathcal{M} \mapsto f(p) \in \mathbb{R} \; , \]

for which \(f \circ \phi_\alpha^{-1}\) is a smooth function on the open neighborhood \(\phi_\alpha (U_\alpha) \subset \mathbb{R}^n\) for all \(U_\alpha\).

An example is provided by the Hamiltonian function \(H\), which assigns a real number to each point of phase space \(\mathbb{P}\), assuming \(H\) to be independent of time. If \(H\) has an explicit time dependence, it assigns a real number to each point of \(\mathbb{P} \times \mathbb{R}_t\), the direct product of phase space and time axis.

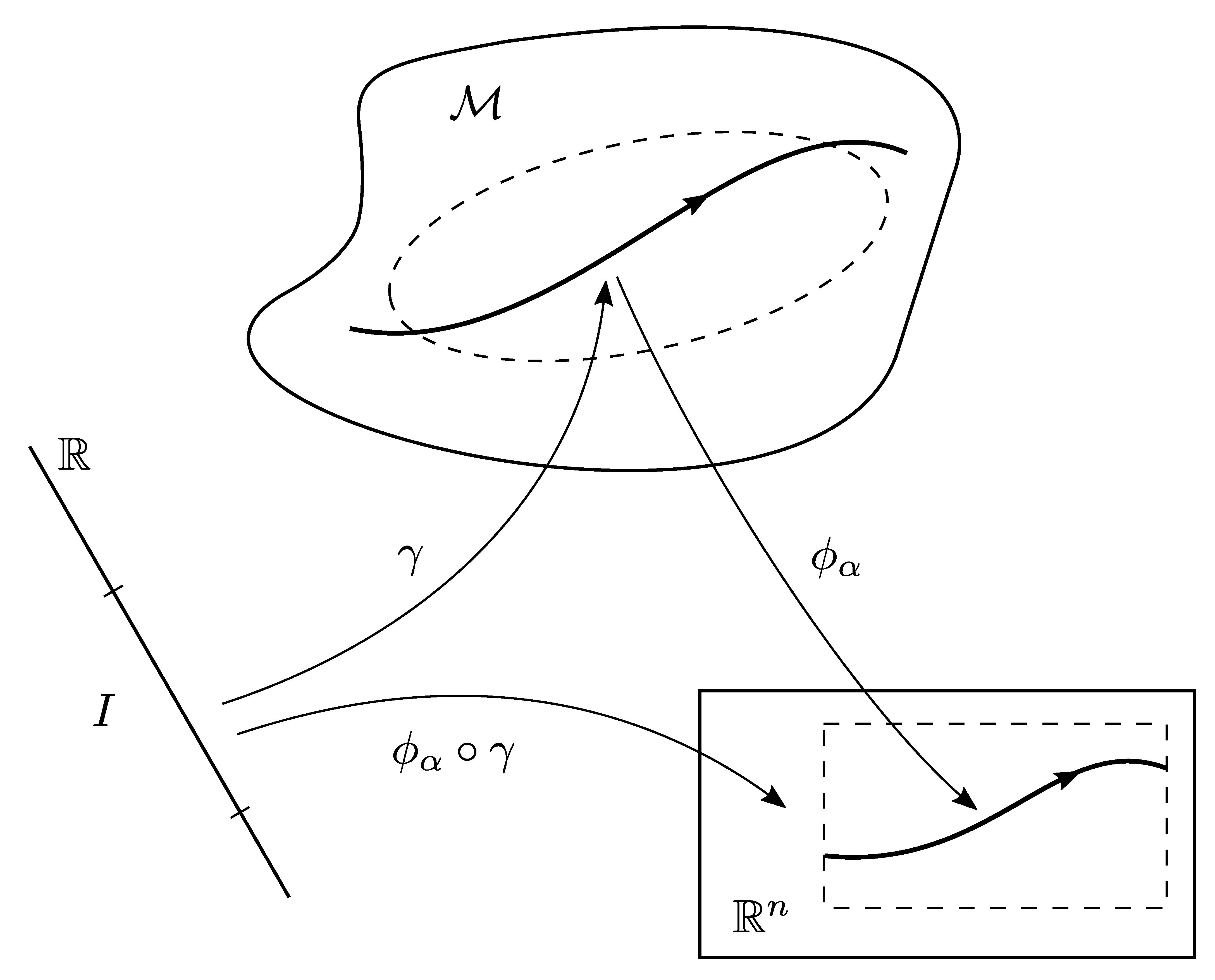

Considered as a mapping, a curve might be thought of as going the opposite way as compared to a function (see Figure 4). Let's look at the example of the orbit of a particle in space and time. A real parameter measuring, say, proper time \(\tau \in \mathbb{R}_\tau\) determines the point \(x(\tau)\) on \(\mathcal{M}\) where the particle is found at time \(\tau\). As \(\tau\) runs along the real axis or an open interval \(I \subset \mathbb{R}_\tau\) the time axis, the particle moves along its one-dimensional orbit in spacetime \(\mathcal{M}\).

A curve is a map

\[\gamma : I \subset \mathbb{R} \to \mathcal{M} : \tau \in I \mapsto \gamma(\tau) \in \mathcal{M}\; ,\]

which assigns a point on \(\mathcal{M}\) to every real number \(\tau\) in the open interval \(I\) on the real axis, \(\tau \in I\).

The curve \(\gamma\) is said to be smooth if its image in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) has the property

\[ (\phi_\alpha \circ \gamma) : I \subset \mathbb{R} \to \phi_\alpha (U_\alpha) \subset \mathbb{R}^n \; . \]

Let's briefly wrap up this section:

We have defined smooth functions \(f\) and smooth curves \(\gamma\) as structures on a manifold \(\mathcal{M}\) in an intrinsic way, using local charts.

Smoothness can be defined as smoothness of restrictions to patches of \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

A function \(f : \mathcal{M} \to \mathbb{R}\) is smooth if its restriction \(f : \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}\) to every chart is smooth.

A curve \(\gamma : \mathbb{R} \to \mathcal{M}\) is smooth if its restriction \(\gamma : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}^n\) to every chart is smooth.

What happens at the intersection of charts? The definition of a smooth manifold contained the requirement that all charts are compatible of class \(C^\infty\), i.e. all chart transitions \(\phi_{\alpha\beta}\) are smooth. Therefore, all charts will agree about the smoothness or otherwise of a function \(f : \mathcal{M} \to \mathbb{R}\) or a curve \(\gamma : \mathbb{R} \to \mathcal{M}\).

Literature

The main sources for this post are the relativity books by Scheck, Straumann, Carroll, and Wald. I also enjoy the lecture notes by Sergei Winitzki, Matthias Bartelmann, Haye Hinrichsen, and Meik Hellmund. Among the mathematical literature, the books by Wolfgang Kühnel and Stephen Lovett are very readable.