Fraunhofer lines are a set of spectral absorption lines named after the German physicist Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787–1826). The lines were originally observed as dark features in the optical spectrum of the Sun by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston in 1802. In 1814, Fraunhofer independently rediscovered the lines and began to systematically study and measure the wavelengths where these features are observed. He mapped over 570 lines, designating the principal features (lines) with the letters A through K and weaker lines with other letters. Modern observations of sunlight can detect many thousands of lines. About 45 years later Kirchhoff and Bunsen noticed that several Fraunhofer lines coincide with characteristic emission lines identified in the spectra of heated elements. It was correctly deduced that dark lines in the solar spectrum are caused by absorption by chemical elements in the solar atmosphere.

Isaac Newton and the Composition of Sunlight

When you let sunlight pass through a prism, you can see that the light is broken up into the colors of the rainbow (a spectrum). The spectrum of the sun had been observed for millennia as rainbows, but was long not recognized as such. It was Isaac Newton who demonstrated that light from the sun was composed of a range of colors that could be separated by a prism.

Newton's 1672 letter to the Royal Society (© The Royal Society)

Newton's 1672 paper on the refraction of light through a prism is now seen as a ground-breaking account and the foundation of modern optics. In it, he claimed to refute Cartesian ideas of light modification by definitively demonstrating that the refrangibility of a ray is linked to its colour, hence arguing that colour is an intrinsic property of light and does not arise from passing through a medium. Previous theories had taken white light for granted and tried to explain how colours are formed. It was thought that the prism itself imparted color on white light. Newton reversed the position by assuming that colour is an inherent property of light, not of the medium it travels through or is reflected from, and that colour can be used to explain white light.

He describes his experiment in the following way:

"I procured me a Triangular glass-Prisme, to try therewith the celebrated Phenomena of Colours. And in thereto having darkened my chamber, and made a small hole in my window-shuts, to let in a convenient quantity of the Suns light, I placed my Prisme at his entrance, that it might be thereby refracted to the opposite wall. It was at first a very pleasing divertisement, to view the vivid and intense colours produced thereby; but after a while applying myself to consider them more circumspectly, I became surprised to see them in an oblong form; which, according to the received laws of Refraction, I expected should have been circular."

The below figures reproduces a sketch made by Newton showing how he converted his study into a large camera obscura by letting a small ray of sunlight pass through a hole in the shutters. His innovation is to use two prisms sequentially. By boring a hole in a screen between them, he singles out individual sections of the first prism's spectrum; these then pass through the second prism to arrive at different places on a second screen. From his demonstration of differential refraction, Newton draws a major theoretical inference: light is ‘a Heterogeneous mixture of differently refrangible rays.’

Newton's sketch of his crucial experiment (© The Royal Society)

Fraunhofer

In 1802, English chemist William Wollaston first noted dark lines in a rainbow caused by sunlight. It was, however, left to a far greater genius than Wollaston independently to rediscover the solar dark line spectrum, to examine and draw it in far greater detail, and to relabel the lines with a nomenclature which, at least for some of them, is still in common use. This genius was Joseph Fraunhofer (1787–1826).

Fraunhofer came from humble parentage in Straubing near Munich and had very little formal education, having lost both parents when he was eleven. In 1807, at the age of 20, he was hired by the Mathematical Mechanical Institute Reichenbach, Utzschneider and Liebherr, a firm founded in 1804 for the production of military and surveying instruments, for which high-quality optical glass for lenses was essential. The optical works of the firm were outside Munich, at a disused monastery in Benediktbeuern. Later, in 1814, the whole firm passed into the hands of Joseph von Utzschneider and Fraunhofer. At this time, about forty people were employed at the Benediktbeuern glass works.

Fraunhofer was a genius at producing optical glasses that were clear and, what is most important, uniform. To take full advantage of these glasses it was essential to know precisely how their refractive index varies with wavelength—their dispersion. To measure dispersion, Fraunhofer invented an intricate differential refractometer that used colored lamps as wavelength standards. In the search for better standards, he dispersed sunlight through a high-quality prism according to the following description:

"Ich stellte nämlich in einem verfinsterten Zimmer ein Prisma aus Flintglas vor dem oben erwähnten Theodolith, und ließ durch eine schmale, ungefähr 15 Sekunden breite und 36 Minuten hohe Oeffnung in dem 24 Fuß vom Prisma entfernten Fensterladen, Sonnenlicht auf dasselbe fallen. Der Winkel des Prisma maß ungefähr 60°, und das Prisma stand so vor dem Objective des Theodolith-Fernrohrs, daß der Winkel des einfallenden Strahles dem Winkel des gebrochenen Strahles gleich war. Ich wollte nun zuerst sehen, ob sich in dem aus Sonnenlicht gebildeten Farbenbilde ein ähnlicher heller Streif, wie in dem Farbenbilde von Lampenlicht zeige; anstatt desselben erblickte ich aber mit dem Fernrohre in diesem horizontal stehenden Farbenbilde fast unzählig viele starke und schwache vertikale Linien, die aber nicht heller, sondern dunkler sind, als der übrige Theil des Farbenbildes, und von denen einige fast ganz schwarz zu seyn scheinen."

To this surprise, he discovered the intricate series of sharp dark lines that now bear his name. He gave the prominent lines across the spectrum alphabetical labels that remain in use today. The C line is the hydrogen Balmer a line, and the D lines (they form a doublet) are due to sodium. Armed with the absorption lines that provide a dense array of wavelength markers, and with his genius at measuring refractive indices, Fraunhofer could determine dispersion with unprecedented precision. Fraunhofer identified more than 570 lines, though only some 350 of these are shown in his below engraving:

Solar spectrum drawn and colored by Joseph von Fraunhofer. Small script in the lower right corner reads "gezeich. u. geäzt von Fraunhofer" (Source: Deutsches Museum)

In this figure he also indicated by the curve the approximate apparent intensity distribution of the light in the spectrum as judged by the eye. In a second paper he was able to measure the wavelengths of the Fraunhofer lines, as the solar absorption lines have since been called. For this he used a diffraction grating consisting of a large number of equally spaced thin wires placed before the objective of the telescope. Fraunhofer was in fact one of the early pioneers in the production of diffraction gratings.

Fraunhofer became convinced that these lines were not an experimental artifact, but were an inherent property of solar light because the lines persisted no matter how he rearranged the distances. Fraunhofer was clever enough to use those dark lines as a natural grid that demarcates minute portions of the spectrum. Refractive indices could now be obtained for an extraordinarily precise portion of the spectrum. He then chose the most obvious (i.e., the thickest and clearest) lines for his determination of the refractive indices of a glass prism, providing opticians and experimental natural philosophers with a vastly more precise method than had ever before been attained.

Fraunhofer founded the field of stellar spectroscopy. He also studied the spectra of flames and electrical discharges and discovered that flames display a bright doublet at the same position as the solar D lines. However, all of Fraunhofer’s discoveries were reported with little or no comment: His true passion was not for science but for making the world’s best optics. He let nothing divert him for long. When he discovered the mysterious dark lines in the solar spectrum, he did not stop to dwell on their origin, but noted towards the end of his publication in Annalen der Physik:

"Bei all meinen Versuchen durfte ich, aus Mangel an Zeit, hauptsächlich nur auf das Rücksicht nehmen, was auf praktische Optik Bezug zu haben schien, und das Uebrige entweder gar nicht berühren, oder nicht weit verfolgen. Da der hier mit physisch-optischen Versuchen eingeschlagene Weg zu interessanten Resultaten führen zu können scheint, so wäre sehr zu wünschen, dass ihm geübte Naturforscher Aufmerksamkeit schenken möchten."

Kirchhoff and Bunsen

While Fraunhofer himself had observed the coincidence of the solar D lines with the bright double line occurring in the spectra of flames, it wasn't until 1860 that Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff connected the wavelengths of light emitted or absorbed to specific chemical elements.

Gustav Kirchhoff noted that the light from a source giving a continuous spectrum, when passed through a powerful salt flame, gave the D lines in absorption. In his 1859 paper Über die Fraunhofer'schen Linien Kirchhoff wrote:

"Ich schließe aus diesen Beobachtungen, daß farbige Flammen, in deren Spectrum helle, scharfe Linien vorkommen, Strahlen von der Farbe dieser Linien, wenn dieselben durch sie hindurch gehen, so schwächen, daß an Stelle der hellen Linien dunkle auftreten, sobald hinter der Flamme eine Lichtquelle von hinreichender Intensität angebracht wird, in deren Spectrum diese Linie sonst fehlen.

Ich schließe weiter, daß die dunklen Linien des Sonnenspectrums, welche nicht durch die Erdatmosphare hervorgerufen werden, durch die Anwesenheit derjenigen Stoffe in der glühenden Sonenatmosphäre entstehen, welche in dem Spectrum einer Flamme helle Linien an demselben Ort erzeugen. Man darf annehmen, daß die hellen, mit D übereinstimmenden Linien im Spectrum einer Flamme stets von einem Natriumgehalt derselben herrühren; die dunklen Linien D im Sonnenspectrum lassen daher schließen, daß in der Sonnenatmosphäre Natrium sich befindet."

The lines in the solar spectrum, therefore, indicated that certain chemical elements were present on the Sun absorbing light. Kirchhoff and Bunsen continued this work carefully in their 1860 paper Chemische Analyse durch Spectralbeobachtungen, which starts with recording the spectra of lithium, sodium, potassium, calcium, strontium and barium salts in flames and sparks. The paper then continues:

"Da es bei der in Rede stehenden analytischen Methode ausreicht, das glühende Gas, um dessen Analyse es sich handeIt, zu sehen, so liegt der Gedanke nahe, dass dieselbe auch auwendbar sei auf die Atmosphäre der Sonne und die helleren Fixsterne. Sie bedarf aber hier einer Modification wegen des Lichtes, welches die Kerne dieser Weltkörper ausstrahlen.

In seiner Abhandlung 'Über das VerhäItnis zwischen dem Emissionsvermögen und dem Absorptionsvermögen der Körper fur Wärme und Licht' hat Einer von uns durch theoretische Betrachtungen nachgewiesen, daß das Spectrum eines glühenden Gases umgekehrt wird, d.h. dass die hellen Linien in dunkele sich verwandeln, wenn hinter dasselbe eine Lichtquelle von hinreichender Intensität gebracht wird, die an sich ein continuirliches Spectrum giebt.

Es lässt sich hieraus schließen, dass das Sonnenspectrum mit seinen dunkeln Linien nichts Anderes ist, als die Umkehrung des Spectrums, welches die Atmosphäre der Sonne für sich zeigen würde. Hiernach erfordert die chemische Analyse der Sonuenatmosphäre nur die Aufsuchung derjenigen Stoffe, die, in eine Flamme gebracht, helle Linien hervortreten lassen, die mit den dunkeln Linien des Sonnenspectrums coincidiren."

This suggestion was carried out in Kirchhoff ’s monumental work which now followed in two parts, the Untersuchungen über das Sonnenspektrum und die Spektren der chemischen Elemente. Kirchhoff carefully drew the solar spectrum and compared this with the spark spectra of 30 different elements. For this purpose he used a 4-prism spectroscope by Steinheil equipped with a collimator to give exceptional spectral purity:

Spektralapparat von Carl August von Steinheil, ca. 1860 (Source: Deutsches Museum)

The apparatus allowed simultaneous viewing of both spark and solar spectra for the most accurate comparison of line positions. Kirchhoff concluded that iron, calcium, magnesium, sodium, nickel and chromium must be present in the cooler outer layers of the Sun, giving the Fraunhofer absorption.

"Noch eine andere Folgerung aus demselben Satze, auf die weiter unten Bezug genommen werden soll, möge hier erwähnt werden. Wenn die Lichtquelle von continuirlichem Spectrum, durch welche das Spectrum eines glühenden Gases umgekehrt werden soll, ein glühender Körper ist, so mufs seine Temperatur höher, als die des glühenden Gases sein. [...]

Um die dunkeln Linien des Sonnenspectrums zu erklären, muss man annehmen, dass die Sonnenatmosphäre einen leuchtenden Körper umhüllt, der für sich allein ein continuirliches Spectrum von einer Lichtstärke giebt, die eine gewisse Grenze übersteigt. Die wahrscheinlichste Annahme, die man machen kann, ist die, dass die Sonne aus einem festen oder tropfbar flüssigen, in der höchsten Glühhitze befindlichen Kern besteht, der umgeben ist von einer Atmosphäre von etwas niedrigerer Temperatur."

Kirchhoff's Laws and Modern Astronomy

The experiments in the early days of spectroscopy revealed that there were three main types of spectra. The differences in these spectra and a description of how to create them can be summarized in Kirchhoff’s three laws of spectroscopy:

Emission spectra are produced by low density, hot gases seen against a cooler background. The atoms do not experience many collisions (because of the low density) and emission lines correspond to photons of discrete energies that are emitted when excited atomic states in the gas make transitions back to lower-lying levels.

A continuum spectrum results from luminous solids, liquids, or dense gases. In dense gases with high pressure lines are broadened by collisions between the atoms until they are smeared into a continuum. We may view a continuum spectrum as an emission spectrum in which the lines overlap with each other and can no longer be distinguished as individual emission lines.

An absorption spectrum occurs when light from a hotter source passes through a cold, dilute gas and atoms in the gas absorb at characteristic frequencies; since the re-emitted light is unlikely to be emitted in the same direction as the absorbed photon, this gives rise to dark lines (absence of light) in the spectrum.

These laws are neatly summarized in the following image:

Kirchhoff's Laws

Like Kepler's laws of planetary motion, these are empirical laws. That is, they were formulated on the basis of experiments. A quantitative understanding of the origin of absorption and emission lines and the spectra that contain these lines only came with the advent of atomic physics.

A star will create an absorption line spectrum because the continuous spectrum emitted by the dense, opaque gas that makes up most of the star passes through the cooler, transparent atmosphere of the star.

The electrons in the gas clouds that create absorption lines should also eventually fall back down to the ground level, so they should also be emitting photons with exactly the same wavelengths as the absorption lines. They do this, but the reason we still observe absorption lines is because the re-emitted photons can be emitted in any direction, while the absorption only occurs along our line of sight.

When you observe an absorption spectrum of an astronomical object, any cloud of gas between us and the object can absorb light. So, when obersving a typical star, you see absorption lines from the atmosphere of the object, you might see absorption lines caused by intervening gas clouds between us and that star, and finally, Earth's atmosphere will also absorb some of the star's light.

A very complete collection of stellar spectra was published by the University of Chicago press in 1943, i.e. An Atlas of Stellar Spectra with an Outline of Spectral Classification, compiled by Morgan, Keenan, and Kellman. The complete contents can be found on-line.

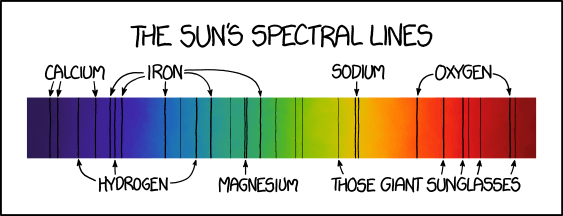

And, as a last fun fact, Fraunhofer lines were also covered in xkcd.com/1733/, which is explained in detail here:

Solar Spectrum according to xkcd.com/1733/

Sources and further reading

Fara, P.: Newton Shows the Light: A Commentary on Newton (1672) 'A Letter … Containing His New Theory About Light and Colours…', Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 373, 2039 (2015). [https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2014.0213]

Fraunhofer, J.: Bestimmung Des Brechungs- Und Des Farbenzerstreungs-Vermögens Verschiedener Glasarten, in Bezug Auf Die Vervollkommnung Achromatischer Fernröhre, Annalen Der Physik 56, 7 (1817). [https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.18170560706] [fulltext]

Hearnshaw, J.B.: The Analysis of Starlight (Cambridge University Press, 2014)

Hennig, J.: Bunsen, Kirchhoff, Steinheil and the Elaboration of Analytical Spectroscopy, Nuncius 18, 2 (2003). [doi:10.1163/182539103x00143]

Jackson, M.W.: Fraunhofer and His Spectral Lines, Annalen Der Physik 526, 7–8 (2014). [https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.201400807]

Kirchhoff, G.: Über die Fraunhofer'schen Linien, Monatsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (1859) [fulltext 1] [fulltext 2]

Kirchhoff, G., Bunsen, R.: Chemische Analyse durch Spectralbeobachtungen, Annalen Der Physik Und Chemie 186, 6 (1860). [https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.18601860602]

Kirchhoff, G.: Untersuchungen über das Sonnenspektrum und die Spektren der chemischen Elemente, Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Berlin (1861) [fulltext]

Kleppner, D.: The Master of Dispersion, Physics Today 58, 11 (2005). [https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2155731]

Newton, I.: A Letter of Mr. Isaac Newton, Professor of the Mathematicks in the University of Cambridge; Containing His New Theory About Light and Colors: Sent by the Author to the Publisher from Cambridge, Febr. 6. 1671/72; in Order to Be Communicated to the R. Society, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 6, 80 (1671). [https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1671.0072]

Palma, C. Penn State ASTRO 801, lecture 3.6