This is a follow-on from a previous post on differentiable manifolds. It is part of a series of posts that I write on the basics of differential or Riemannian geometry, providing the necessary background for reading some of the more advanced textbooks on general relativity. The following posts will cover tensors, covariant derivatives and parallel transport. The presentation will be informal, focusing mostly on motivation, definitions and key facts, not on mathematical proofs.

Many laws of physics are stated through vectorial equations, which suggests that also on abstract manifolds it should be desirable to be able to define and manipulate vectors. In ordinary physics, vectors are used to specify 'directed magnitudes', such as velocities and forces. Therefore, it is important to develop the concept of a 'directed magnitude' in a curved space.

In the local theory of regular surfaces \(S \subset \mathbb{R}^3\), an immediate example of a 'directed magnitude' comes from considering the velocity of a moving point. Let us imagine a point that moves along a curve \(\gamma(\tau)\) within \(S\), where \(\gamma\) is a map \(I \subset \mathbb{R} \rightarrow S\). The velocity of the moving point is a vector (in the larger space \(\mathbb{R}^3\)) that is always tangent to the surface \(S\). Due to this picture, 'directed magnitudes' defined within a curved surface or manifold are also called tangent vectors or simply vectors.

At every point \(p\) of the surface or manifold there is a tangent plane, which is a vector subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^{3}\). In the local theory of regular surfaces \(S \subset \mathbb{R}^3\), the tangent plane plays a particularly important role. The first fundamental form on the tangent plane is defined as the restriction of the dot product in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) to the tangent. From the coefficients of the first fundamental form, one obtains all the concepts of intrinsic geometry, which include angles between curves, areas of regions, Gaussian curvature, geodesics, etc.

In order to make sense of calculus on abstract manifolds, we need to introduce the tangent space to a manifold at a point, which we can think of as a sort of 'linear model' for the manifold near the point. Because of the abstractness of the definition of a smooth manifold, this can become quite an intricate procedure in the mathematical literature. There one can find several different, but equivalent ways to define tangent vectors to a smooth manifold:

Different ways to define tangent vectors to a manifold \(\mathcal{M}\):

Algebraic definition: Tangent vectors as derivations of the space of germs. Briefly: Tangent vectors are derivations acting on scalar functions.

Geometric definition: Tangent vectors as equivalence classes of differentiable curves. Briefly: Tangent vectors are tangents to curves lying on the manifold.

Physicist's definition: Tangent vectors as equivalence classes of coordinate \(n\)-tuples. Briefly: Tangent vectors are elements of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) with a particular transformation behavior. Or stated differently: An object is a vector if it transforms like a vector.

It is a matter of individual taste which of the various characterizations of \(T_p \mathcal{M}\) one chooses to take as the definition. The algebraic definition, however abstract it may seem at first, has several advantages: it is relatively concrete (tangent vectors are actual derivations of \(C^\infty(\mathcal{M})\), with no equivalence classes involved); it makes the vector space structure on \(T_p \mathcal{M}\) obvious; and it leads to straightforward coordinate-independent definitions of differentials, velocities, and many of the other geometric objects.

In the following paragraphs, we follow more or less the algebraic track, but in simple practical steps. The task is to construct the tangent space at a point \(p\) in a manifold \(\mathcal{M}\), without an embedding in a higher-dimensional space, using only things that are intrinsic to \(\mathcal{M}\). Two relevant concepts we had introduced previously are curves \(\gamma: I \subset \mathbb{R} \to \mathcal{M}\) and functions \(f: \mathcal{M} \to \mathbb{R}\).

One first guess might be to use our intuition that there are objects called 'tangent vectors to curves' which belong in the tangent space. We might therefore consider the set of all parameterized curves through \(p\), that is, the space of all (nondegenerate) maps \(\gamma: I \subset \mathbb{R} \to \mathcal{M}\) such that \(p\) is in the image of \(\gamma\). The temptation is to define the tangent space as simply the space of all tangent vectors to these curves at the point \(p\). But this is obviously cheating; the tangent space \(T_p\) is supposed to be the space of vectors at \(p\), and before we have defined this we don't have an independent notion of what 'the tangent vector to a curve' is supposed to mean.

We could try to define a tangent vectors as the 'directed velocities' \(d\gamma/d\tau\) of the curves \(\gamma(\tau)\) going through \(p\). However, we cannot directly differentiate \(\gamma(\tau)\) with respect to \(\tau\) without an embedding because the expression \(\gamma(\tau+\delta)-\gamma(\tau)\) is undefined: we cannot 'subtract' one point from another. To circumvent this difficulty, we must take a step in the direction of abstraction. We will focus not on points but on functions of points.

The strategy is to define a tangent vector as a directional derivative at a point \(p\) of a real-valued function on a manifold \(\mathcal{M}\). Furthermore, since we cannot use vectors in an ambient Euclidean space to provide the notion of direction, we simply talk about curves on \(\mathcal{M}\) through \(p\) as providing a notion of direction. The following construction makes this precise.

Definition.

Let \(\mathcal{M}\) be a differentiable manifold, \(p\) be a point on \(\mathcal{M}\), and let \(U\) be an open neighborhood of \(\mathcal{M}\). Let \(\epsilon > 0\), and let \(\gamma : (-\epsilon, \epsilon) \to U\) be a differentiable curve on \(\mathcal{M}\) such that \(\gamma(0) = p\). For any differentiable function \(f : U \subset \mathcal{M} \to R\), we define the directional derivative of \(f\) along \(\gamma\) to be the number

\[\textrm{D}_{\gamma}f(p) = \left.\frac{d}{d\tau}\right|_{\tau=0}f(\gamma(\tau)) \;.\]

This derivative is interpreted as the instantaneous rate of change of the function \(f\) at point \(p\), as one moves along the curve \(\gamma\) passing through \(p\). The operator \(\textrm{D}_{\gamma}\) is called the tangent vector to \(\gamma\) at \(p\).

Some remarks are in order:

The above definition does not explicitly refer to any particular chart on \(U\).

The function \(f\) is merely a test function. We could choose any other function to test how things change with movement along \(\gamma\). What is important is not which function we choose, but how the curve \(\gamma\) causes it to change with movement along \(\gamma\) away from \(p\).

Also the curve \(\gamma\) plays only an auxiliary role, there is no preferred choice. In fact, there are infinitely many curves that have the same tangent at \(\tau = 0\) and give the same directional derivative.

The function \(f\circ\gamma\) maps \((-\epsilon, \epsilon) \to U\), so the derivative is taken as a usual real function.

If \(\gamma_1\) and \(\gamma_2\) are two curves, then we set \(\textrm{D}_{\gamma_1} = \textrm{D}_{\gamma_2}\) if these operators have the same value at \(p\) for all differentiable functions \(f : U \to R\).

In the words of MTW, it is 'preposterous' that vectors have morphed from a geometrical concept into a derivative operator (or derivation), represented by the mnemonic

\[\textrm{D}_\gamma = \mathbf{v} = \partial_\mathbf{v} =\left.\frac{d}{d\tau}\right|_\text{along curve} \ .\]

We will preferably denote vectors by boldface letters such as \(\mathbf{v}\) or even plain letters such as \(v\) rather than operators \(\textrm{D}_\gamma\).

Common notations for the action of \(\mathbf{v}\) on \(f\) are \(\mathbf{v}(f)\), or \(\mathbf{v} \circ f\), or simply \(\mathbf{v} f\). Note again that \(\mathbf{v}(f)\) is a real number. Sometimes you can also find the notation \(\textrm{D}_\gamma f = \dot{\gamma} \circ f\), where \(\dot{\gamma}\) means the tangent vector to the curve \(\gamma\).

Let's try to get a better intuition and check whether we are on the right way to defining the tangent space as the 'space of all possible directional derivatives.'

For that purpose, we introduce a local coordinate chart \(x^\mu\) around the point \(p\). There is an obvious set of \(n\) directional derivatives at \(p\), namely the partial derivatives \(\partial_\mu\) at \(p\). Note that this is really the definition of the partial derivatives with respect to \(x^\mu\): the directional derivative along a curve defined by \(x^\nu\) = constant for all \(\nu =\not\, \mu\), parameterized by \(x^\nu\) itself.

We are now going to claim that the partial derivative operators \(\partial_\mu\) at \(p\) form a basis for the tangent space \(T_p\). To see this we will show that any directional derivative can be decomposed into a sum of real numbers times partial derivatives.

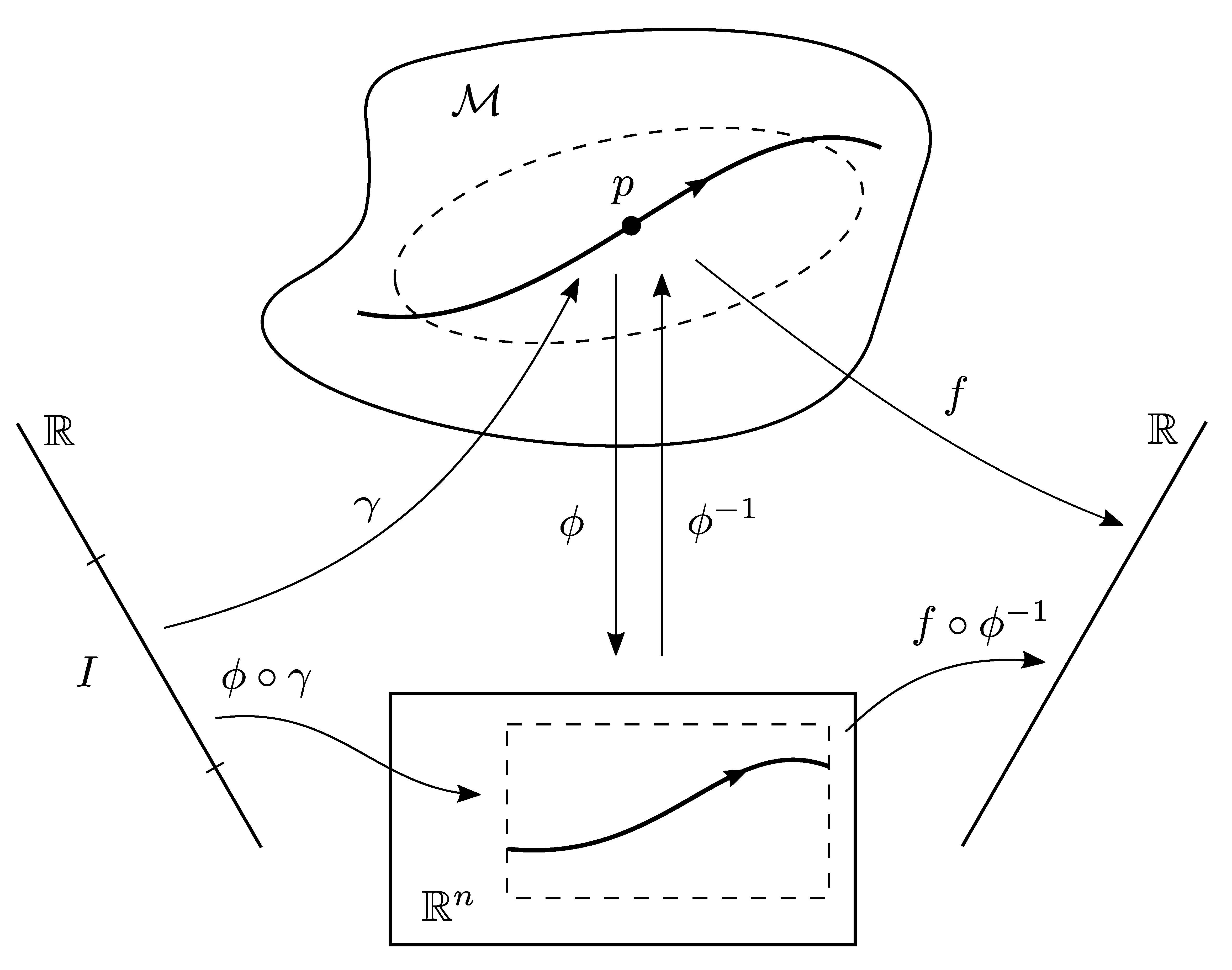

It's nice to see it from the big-machinery approach. Consider an \(n\)-manifold \(\mathcal{M}\), a coordinate chart \(\phi:\mathcal{M}\rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n\), a curve \(\gamma:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow \mathcal{M}\), and a function \(f:\mathcal{M}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\); see the figure below:

If \(\tau\) is the parameter along \(\gamma\), we want to expand the operator \(d/d\tau\) in terms of the partials \(\partial_\mu\). Using the chain rule we have

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{d}{d\tau} f(p) &= \frac{d}{d\tau}(f\circ\gamma)\Big|_{\tau=0} \\[0.5em] &= \frac{d}{d\tau} \big((f\circ\phi^{-1})\circ(\phi\circ\gamma)\big)\Big|_{\tau=0} \\[0.5em] &= \frac{d(\phi\circ\gamma)^\mu}{d\tau}\Big|_{\tau=0} \ \frac{\partial(f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial x^\mu}\Big|_{\phi(p)} \\[0.5em] &= \frac{dx^\mu}{d\tau} \Big|_{\tau=0} \ \frac{\partial}{\partial x^\mu} \Big|_{p} \ f \; . \end{aligned} \]

The first line simply takes the informal expression on the left hand side and rewrites it as an honest derivative of the function \((f\circ\gamma):\mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). The second line just comes from the definition of the inverse map \(\phi^{-1}\) (and associativity of the operation of composition). The third line is the formal chain rule, and the last line is a return to the informal notation of the start. Since the function \(f\) was arbitrary, we have

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{d}{d\tau} &= \frac{dx^\mu}{d\tau} \ \partial_\mu \ , \quad \text{or} \\[0.7em] \mathbf{v} \; &= \ \ v^\mu \ \ \partial_\mu \ . \end{aligned} \]

We see that directional derivatives \(d/d\tau\) are described by a set of coefficients \(d x^\mu/d\tau\) multiplying a fixed set of differential operators \(\partial_\mu\). The coefficients \(d x^\mu/d\tau\) depend on the curve \(\gamma\), while the operators \(\partial_\mu\) do not. Therefore, it is natural to regard \(\partial_\mu\) as the basis in the vector space of directional derivatives and \(d x^\mu/d\tau\) as the components of \(d/d\tau\) in that basis.

The vector represented by \( \mathbf{v} = d/d\tau\) is the tangent vector to the curve \(\gamma\) with parameter \(\tau\) on an arbitrary manifold, where we have specified our basis vectors to be \( \hat{e}_{(\mu)}=\partial_\mu\). This particular basis is known as a coordinate basis for \(T_p\); it is the formalization of the notion of setting up the basis vectors to point along the coordinate axes. There is no reason why we are limited to coordinate bases when we consider tangent vectors; it is sometimes more convenient, for example, to use orthonormal bases of some sort. However, the coordinate basis is very simple and natural, and is used almost exclusively throughout the literature.

As suggested by the name 'tangent vector' and by the split of directional derivatives into basis vectors and components indicated above, the set of all tangent vectors forms a vector space, a fact that we want to show now. In the first place, it is fairly easy to see that the collection of tangent vectors \(\textrm{D}_\gamma\) at \(p\) has the structure of a vector space under addition and scalar multiplication.

Let's start with scalar multiplication first. Let \(\gamma: (-\epsilon,\epsilon) \to \mathcal{M}\) be a differentiable curve with \(\gamma(0) = p\). If we define \(\gamma_1(\tau) = \gamma(a\tau)\), where \(a\) is some real number, then using the usual chain rule for any differentiable function \(f \in C^1(U, \mathbb{R})\), we have

\[ \textrm{D}_{\gamma_1}f(p) = \frac{d}{d\tau} f \big(\gamma(a\tau)\big) \Big|_{\tau=0} = a \frac{d}{d\tau} f \big(\gamma(\tau)\big) \Big|_{\tau=0} = a\, \textrm{D}_{\gamma}f(p) \ . \]

This shows that the set of tangent vectors is closed under scalar multiplication. In order to prove that the set of tangent vectors is closed under addition, we make reference to a coordinate chart \(\phi:U\to\mathbb{R}^n\). As shown above, we have

\[ \textrm{D}_{\gamma}f(p) = \frac{\partial(f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial x^\mu}\Big|_{\phi(p)} \ \frac{d(\phi\circ\gamma)^\mu}{d\tau}\Big|_{\tau=0} \ . \]

Now let \(\phi:U\to\mathbb{R}^n\) be a coordinate chart of a neighborhood of \(p\) on \(\mathcal{M}\) such that \(\phi(p) = (0,\cdots,0)\). Let \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) be two differentiable curves on \(\mathcal{M}\) such that \(\alpha(0) = \beta(0) = p\). Over the intersection of the domains of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), define the curve \(\gamma\) by

\[\gamma(\tau) = \phi^{-1} \big(\phi\circ\alpha(\tau) + \phi\circ\beta(\tau) \big) \ .\]

Then for any function \(f:U\to\mathbb{R}\), we have

\[ \begin{aligned} \textrm{D}_\alpha&(f) + \textrm{D}_\beta(f) = \\[0.5em] &= \frac{\partial(f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial x^\mu}\Big|_{\phi(p)} \frac{d(\phi\circ\alpha)^\mu}{d\tau}\Big|_{\tau=0} + \frac{\partial(f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial x^\mu}\Big|_{\phi(p)} \frac{d(\phi\circ\beta)^\mu}{d\tau}\Big|_{\tau=0} \\[0.5em] &= \frac{\partial(f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial x^\mu}\Big|_{\phi(p)} \left(\frac{d(\phi\circ\alpha)^\mu}{d\tau}\Big|_{\tau=0} + \frac{d(\phi\circ\beta)^\mu}{d\tau}\Big|_{\tau=0} \right) \\[0.5em] &= \frac{\partial(f\circ\phi^{-1})}{\partial x^\mu}\Big|_{\phi(p)} \frac{d}{d\tau}\Big|_{\tau=0} \big(\phi\circ\alpha(\tau) + \phi\circ\beta(\tau) \big)^\mu \\[0.5em] &= \textrm{D}_\gamma(f) \ . \end{aligned} \]

Let's pause for a moment and wrap up what we have done so far, before we become even more formal and outline the connection to initially stated algebraic definition, according to which a vector is a derivation of the space of germs.

Summary of what happened so far, for orientation.

We strive to establish the concept of a (tangent) vector to a manifolds as a local concept, without reference to a higher-dimensional embedding, through a limiting process.

A limiting process requires the notion of 'closeness'. Such a notion requires the concept of distance, which is not essential for a general manifold, but could be provided by introducing a metric. However, the concept of a vector is too general to require such an elaborate structure as a metric.

We had previously defined two concepts for manifolds, more basic than the concept of a metric, that together can help us define a vector as a limit: (real-valued) functions \(f\) and and curves \(\gamma\) can be combined to a real-value function on \(\mathbb{R}\), the composition \(f\circ\gamma : \mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\).

The derivative \(\textrm{D}_\gamma(f) = d(f\circ\gamma)/d\tau\) is the usual derivative of an ordinary function of one variable. The function \(f\) is merely a test function, what is important is how the curve \(\gamma\) causes the function to change with movement along \(\gamma\) away from the point \(p\). This change is determined by the directional derivative along \(\gamma\) at \(p\).

Since the function \(f\) is merely a test function, we can now view the derivation \(\textrm{D}_\gamma = d/d\tau\) as the tangent vector \(\mathbf{v}\) to the curve. The process of taking directional derivatives gives a natural one-to-one correspondence between geometric tangent vectors and derivations, i.e. linear maps from smooth functions to \(\mathbb{R}\) satisfying the product rule.

With this as motivation, we then define a tangent vector \(\mathbf{v}\) on a smooth manifold as a derivation. As such, it is \(\mathbb{R}\)-linear and fulfills the Leibniz product rule, precisely because the partial derivatives \(\partial_\mu\) have these properties:

- \(\mathbf{v} (af+bg) = a\mathbf{v}(f) + b\mathbf{v}(g) \quad\) for all \(f,g \in C^\infty(\mathcal{M}); a,b \in \mathbb{R};\)

- \(\mathbf{v}_p(fg) = f(p) \mathbf{v}_p(g) + \mathbf{v}_p(f) g(p)\).

The set of tangent vectors at \(p\) has the structure of a vector space under addition and scalar multiplication:

- \((\mathbf{v_1}+\mathbf{v_2})(f) = \mathbf{v_1}(f) + \mathbf{v_2}(f)\);

- \((a\mathbf{v})(f) = a\mathbf{v}(f)\).

After these more or less down-to-earth considerations, we now lift off for some mathematical terminology, the formal definition of an (algebraic) tangent vector, and a theorem. Not much concrete insight will be gained here, but collecting this stuff in one place may help in future when thumbing through relevant mathematical monographs.

A relation on a set \(S\) is a subset \(R\) of \(S \times S\). Given \(x,y\) in \(S\), we write \(x \sim y\) iff \((x,y) \in R\). The relation \(R\) is an equivalence relation if it satisfies the following three properties for all \((x,y,z) \in S\):

- \(x \sim x\) (reflexivity),

- if \(x \sim y\), then \(y \sim x\) (symmetry),

- if \(x \sim y\) and \(y \sim z\), then \(x \sim z\) (transitivity).

As long as two functions agree on some neighborhood of a point \(p\), they will have the same directional derivatives at \(p\). This suggests that we introduce an equivalence relation on the \(C^\infty\) functions defined in some neighborhood of \(p\). Consider the set of all pairs \((f,U)\), where \(U\) is a neighborhood of \(p\) and \(f : U \to R\) is a \(C^\infty\) function. We say that \((f,U)\) is equivalent to \((g,V)\), or \((f,U) \sim (g,V)\), if there is an open set \(W\subset U \cap V\) containing \(p\) such that \(f=g\) when restricted to \(W\). In other words, \(f\) and \(g\) are equivalent if they 'conincide' on some neighborhood \(W\) of \(p\). This is clearly an equivalence relation because it is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

The equivalence class of \((f,U)\) is called the germ of \(f\) at \(p\), sometimes denoted by \([(f,U)]\) or \([f]_p\). Another notation indicates a germ by an overline, \(\overline{f}\), to distinguish the function \(f\) from the germ \(\overline{f}\) it is representing. Most texts, however, skip this notational finesse for the following reason: while a function \(f\), defined on a neighborhood \(U\) of \(p\in\mathcal{M}\), contains more information than the germ \(\overline{f}\) at \(p\), the germ is sufficient for all operations which only require any neighborhood around \(p\), irrespective of its size.

The set of all germs of functions at a point \(p\in\mathcal{M}\) is denoted by \(C^\infty_p(\mathcal{M})\), or simply \(C^\infty_p\), or \(\mathcal{F}_p\mathcal{M}\), or simply \(\mathcal{F}_p\). It has the structure of a real algebra, provided the operations addition and multiplication are defined naturally via the corresponding operations on representatives (i.e. the functions \(f,g,\dots\)).

An algebra over a field \(K\) is a vector space \(A\) over \(K\) with a multiplication map \(\mu : A \times A \to A\), usually written \(\mu(a,b) = a \cdot b\), such that for all \(a,b,c \in A\) and \(r \in K\),

- \((a \cdot b) \cdot c = a \cdot (b \cdot c) \quad \) (associativity),

- \((a+b) \cdot c= a\cdot c+b\cdot c \; \text{and} \; a \cdot (b+c) = a\cdot b+a\cdot c \quad\) (distributivity),

- \(r(a\cdot b) = (ra)\cdot b = a\cdot(rb) \quad\) (homogeneity).

Thus, an algebra has three operations: the addition and multiplication of a ring and the scalar multiplication of a vector space. Usually we omit the multiplication sign and write \(ab\) instead of \(a\cdot b\). The addition and multiplication of functions induce corresponding operations on \(\mathcal{F}_p\), making it into an algebra over \(\mathbb{R}\).

A linear map or linear operator is a map \(L:V \to W\) between vector spaces over a field \(K\) if, for any \(r \in K\) and \(u,v \in V\),

- \(L(u+v) = L(u) + L(v)\),

- \(L(rv) = rL(v)\).

To emphasize the fact that the scalars are in the field \(K\), such a map is also said to be K-linear. If \(A\) and \(A'\) are algebras over a field \(K\), then an algebra homomorphism is a linear map \(L: A \to A'\) that preserves the algebra multiplication: \(L(ab) = L(a)L(b)\) for all \(a,b \in A\).

A derivation of \(\mathcal{F}(p)\) is a linear map \(\mathbf{v} : \mathcal{F}(p) \to \mathbb{R}\) which satisfies the Leibniz (product) rule \(\mathbf{v}_p(fg) = f(p) \mathbf{v}_p(g) + \mathbf{v}_p(f) g(p)\).

That being said, we can now precisely define tangent space and tangent vectors, 'the algebraic way':

The tangent space \(T_p\mathcal{M}\) of a differentiable manifold \(\mathcal{M}\) at a point \(p\) is the set of derivations defined on the set of germs of functions \(\mathcal{F}_p \mathcal{M}\), in other words the set of operators \(\mathbf{v}_p : \mathcal{F}_p\mathcal{M} \to \mathbb{R}\) that are \(\mathbb{R}\)-linear and satisfy the Leibniz-property

- \(\mathbf{v}_p (af+bg) = a\mathbf{v}_p(f) + b\mathbf{v}_p(g)\),

- \(\mathbf{v}_p(fg) = f(p) \mathbf{v}_p(g) + \mathbf{v}_p(f) g(p)\),

for all \(f,g \in \mathcal{F}_p\mathcal{M}, a,b \in \mathbb{R}\). The vector space operations in \(T_p\mathcal{M}\) are defined by

- \((\mathbf{v}_p+\mathbf{w}_p)(f) = \mathbf{v}_p(f) + \mathbf{w}_p(f)\),

- \((a\mathbf{v}_p)(f) = a\mathbf{v}_p(f)\).

A tangent vector to \(\mathcal{M}\) at \(p\) is any \(\mathbf{v}_p \in T_p\mathcal{M}\).

Next we can prove two properties of derivations.

Lemma: Let \(\mathbf{v}\) be a tangent vector to \(\mathcal{M}\) at \(p\). If \(f \in \mathcal{F}\mathcal{M}\) is constant in some neighborhood of \(p\), then \(\mathbf{v}(f) = 0\).

Proof: First consider the function \(\mathit{1}\) that takes the value \(1\) everywhere on \(\mathcal{M}\). Then, according to the Leibniz-property, \(\mathbf{v}(\mathit{1}) = \mathbf{v}(\mathit{1} \cdot \mathit{1}) = 1 \cdot \mathbf{v} (\mathit{1}) + 1 \cdot \mathbf{v} (\mathit{1}) = 2 \cdot \mathbf{v} (\mathit{1})\), so that \(\mathbf{v} (\mathit{1}) = 0\). But then for every constant function \(f = c \cdot \mathit{1}\) \((c \in \mathbb{R})\), according to linearity, \(\mathbf{v}(f) = \mathbf{v} (c \cdot \mathit{1}) = c \cdot \mathbf{v} (\mathit{1}) = 0. \)

Lemma: Let \(\mathbf{v}\) be a tangent vector to \(\mathcal{M}\) at \(p\) and suppose that \(f\) and \(g\) are elements of \(\mathcal{FM}\) that agree on some neighborhood of \(p\) in \(\mathcal{M}\). Then \(\mathbf{v}(f) = \mathbf{v}(g)\).

Proof: Let \(h := f-g\) in a neighborhood \(U \in \mathcal{M}\) of \(p\). We may select a bump function \(\sigma \in \mathcal{FM}\) with \(\sigma(p)=1\) on \(U\) and \(\sigma=0\) outside \(U\). Then \(\sigma h = 0\) on all of \(\mathcal{M}\) and, by the product rule, \( 0 = \mathbf{v}(\sigma h) = \sigma(p) \mathbf{v}(h) + h(p) \mathbf{v}(\sigma) = \mathbf{v}(h) \ , \) since \(\sigma(p)=1\) and \(h(p)=0\). But then \( 0 = \mathbf{v}(h) = \mathbf{v}(f-g) = \mathbf{v}(f) - \mathbf{v}(g) \) and thus \(\mathbf{v}(f) = \mathbf{v}(g)\).

This second Lemma implies that the value of \(\mathbf{v}(f)\) only depends on the behavior of \(f\) on arbitrarily small neighborhoods of \(p\). It is therefore sufficient to base the definition of tangent vectors just on \(\mathcal{F}_p\mathcal{M}\) instead of \(\mathcal{FM}\).

With this preparation we can prove the following theorem.

Let \(\mathcal{M}\) be a differentiable manifold and \(p \in \mathcal{M}\). If \((U,\phi)\) is a chart at \(p\) with coordinate functions \(x^1,\ldots,x^n\), then

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial x^1}\Big|_p, \ldots, \frac{\partial}{\partial x^n}\Big|_p \]

is a basis for the tangent space \(T_p\mathcal{M}\). Moreover, for each vector \(\mathbf{v} \in T_p\mathcal{M}\),

\[ \mathbf{v} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \mathbf{v}(x^i) \frac{\partial}{\partial x^i}\Big|_p = \sum_{i=1}^{n} v^i \frac{\partial}{\partial x^i}\Big|_p \overset{\text{s.c.}}{=} v^i \frac{\partial}{\partial x^i}\Big|_p \ . \]

Proof:

(i) Without loss of generality, we may assume that \(\phi(p) = (x^1(p), \ldots, x^n(p)) = (0, \ldots, 0) \ ,\) and that \(\phi(U)\) is the open \(r\)-ball \(B_r(0)\) about \(0 \in \mathbb{R}^n\) (see Naber, p. 248).

(ii) The vectors \(\partial x^1|_p, \ldots, \partial x^n|_p\) are linearly independent. To see this, we apply \(0 = \sum_{i=1}^{n} a^i \partial_i |_p\), with \(a^1, \ldots, a^n \in \mathbb{R}\), to the coordinate function \(x^k\):

\[ 0 = \left( \sum_{i=1}^{n} a^i \partial_i |_p \right) x^k = \sum_{i=1}^{n} a^i \frac{\partial x^k}{\partial x^i} \Big|_p = \sum_{i=1}^{n} a^i \delta_i^k = a^k \ . \]

(iii) Next we need a preliminary result from calculus. Let \(g\) be a real-valued smooth function on the open ball \(B_r(\mathbf{0})\) about \(\mathbf{0}\) in \(\mathbb{R}^n\). We show that, for \(\mathbf{x} \in B_r(\mathbf{0})\), \(g\) can be written \(g(\mathbf{x}) = g(\mathbf{0}) + x^i g_i(\mathbf{x})\) (summation convention!), where \(x^i\) are the standard coordinates in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) and each \(g_i(\mathbf{x})\) is smooth. To prove this note first that, for each \(\mathbf{x} \in B_r(\mathbf{0})\) and each \(t \in [0,1]\), \(t\mathbf{x}\) is in \(B_r(\mathbf{0})\). Further note that \(d_t \, g(t\mathbf{x}) = \partial_i \, g(t\mathbf{x}) x^i dt\), so the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus gives

\[ g(\mathbf{x}) - g(\mathbf{0}) = \int_0^1 \partial_i \, g(t\mathbf{x}) x^i dt = x^i \int_0^1 \partial_i \, g(t\mathbf{x}) dt \ = x^i g_i(\mathbf{x}) \ , \]

if we let \(g_i(\mathbf{x}) = \int_0^1 \partial_i \, g(t\mathbf{x}) dt\). One can show (see Naber p. 248) that the \(g_i(\mathbf{x})\) are smooth.

(iv) Now, let's use the following set-up: a function \(f:\mathcal{M} \to \mathbb{R}\), a chart \(\phi: U \to V\), with \(B_r(0) \subset V=\phi(U)\), and a smooth coordinate expression for \(f\), which we name \(g\), with \(g=f\circ\phi^{-1}:B_r(0)\to\mathbb{R}\). We have

\[ \begin{aligned} f(p)&=(f\circ\phi^{-1})\circ(\phi(p))=g\circ(\phi(p)) \\[0.5em] &=g(\phi(p))=g(\mathbf{0}) \quad \text{and} \\[0.5em] f(q)&=g(\phi(q))=g(\mathbf{x}) \quad \text{for an arbitary point } q\in U . \end{aligned} \]

Corresponding to \(f=g\circ\phi\) we define component functions \(f_i=g_i\circ\phi \in \mathcal{F}_p\). With the preparation from paragraph (iii) we have

\[ \begin{aligned} f_i(p)&=g_i(\mathbf{0})=\int_0^1 \partial_i \, g(t\mathbf{0}) dt = \int_0^1 \partial_i \, g(\mathbf{0}) dt \\[0.5em] &= \partial_i \, g(\mathbf{0}) = \partial_i (f\circ\phi^{-1})(\mathbf{0}) = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x^i} \Big|_p \ . \end{aligned} \]

(v) We now show the identity \(\mathbf{v} = \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{v}(x^i) \partial_i = v^i \partial_i\) for any vector \(\mathbf{v} \in T_p\mathcal{M}\), or

\[ \mathbf{v}f = \sum_{i=1}^{n} v^i \frac{\partial f}{\partial x^i} \Big|_p \quad \text{for all} \quad f \in \mathcal{F}_p \mathcal{M} \ . \]

Using

\[ \begin{aligned} f(q)&=g(\phi(q))=g(\mathbf{x})= g(\mathbf{0}) + x^i g_i(\mathbf{x}) \\[0.5em] &=f(p) + x^i g_i(\mathbf{x}) =f(p) + x^i f_i(q) \end{aligned} \]

we have, since \(f(p)\) and \(f_i(q)\) are constant functions,

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{v}f(q) &= \mathbf{v}\big(f(p) + x^i f_i(q)\big) \\[0.5em] &= \mathbf{v}\big(f(p)\big) + x^i \, \mathbf{v}\big(f_i(q)\big) + f_i(q) \mathbf{v}(x^i) \\[0.5em] &= 0 + 0 + v^i f_i(q) \\[0.5em] &= v^i \frac{\partial f}{\partial x^i}\Big|_q \ . \end{aligned} \]

Since both \(f \in \mathcal{F}_p\) and \(q \in U\) were arbitrary, the theorem holds.

Literature

The main sources for the first half of this post are the books by Sean Carroll and Stephen Lovett, and the lecture notes by Sergei Winitzki. The more mathematical second half draws heavily on the books by Gregory Naber and Fischer/Kaul, but I also consulted books by John Lee, Klaus Jänich, and Norbert Straumann.